Why is the Missing Middle... missing?

We have some reasons and we wrote them down.

This one is maybe a tiny bit more ‘inside baseball’ than I normally do here. I tried my hardest to combat the dry subject matter, but the matter is so very dry — so I may have bitten off more than I could chew (as usual). Did I succeed? Only you can make that call.

Cities used to be different

Have you ever been to a city that’s reasonably old? By old, I mean a city that was mostly developed in the period known as B.C. — Before Cars.

You’ll notice that the housing from this period looks different. I’m talking of course about the gorgeous terrace homes and low-rise apartments of London, New York, Paris, Sydney, Boston, Edinburgh and many more.

Now contrast these older cities with our much newer Australian cities. Those types of housing seem to be the only thing we don’t build in established urban areas. In Australia, we tend to live in high rise apartments, or languish in suburban estates, with precious little options in between - except on the farthest reaches of the urban fringe.

As the story goes, the car came along, and urban growth was no longer constrained by the tyranny of distance; higher density living became unnecessary. We could spread out in every direction and still live a reasonable distance from the CBD. There was no reason to go without a suburban house and land combo – everyone was a winner.

This also created a massive expansion of middle class wealth, where millions of normal Australians enriched themselves through doing what they wanted to do anyway — buying their forever home.

The suburban salad days are almost over

But now, we are fast approaching the logical end point of this paradigm.

In many instances, we have expanded so far outwards that the limits of the suburban frontier have been reached, with massive commutes required of the people on the outer fringes. In many instances, the outer suburbs are significantly more dense than inner suburbs. This is bad for so many reasons.

Meanwhile, the mass proliferation of knowledge work means that if you want to achieve any modicum of success in a white-collar career, you are well and truly shackled to one of Australia’s 3-5 capital cities — with no guarantees that your wage will land you a home anywhere near your job. The Knowledge Economy has forced Australians to compete with each other and international investors in a bloodthirsty free-for-all over a relatively fixed amount of increasingly unaffordable properties. In the past, many more people would have sought to live and work in the regions.

We can no longer go out, so we must go up

With precious few remaining places to expand outwards, the next evolution of Australian cities will be to expand inwards and upwards — that is, densifying desirable inner and middle ring suburbs so that more people can benefit from proximity to existing employment centres, infrastructure and amenities. Consolidation!

Wait!.. Sir!.. Please!.. Put down the gun!

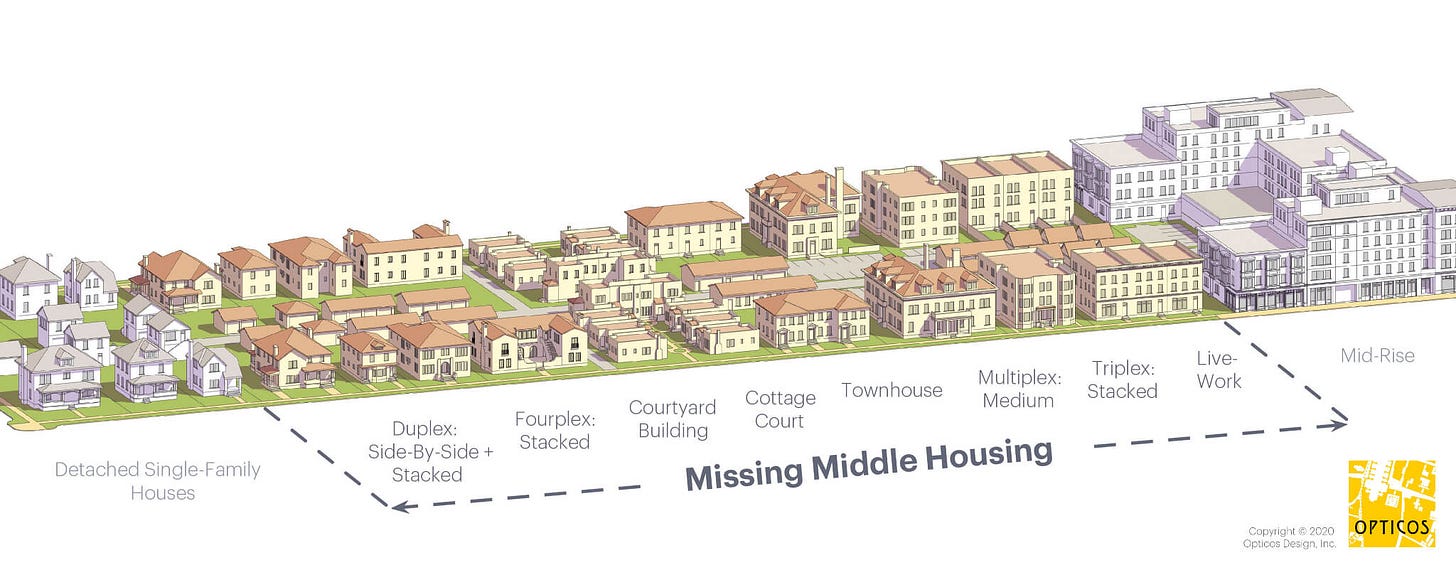

I don’t mean we’re all going to live in high rise apartments. That’s not necessary; we won’t be in South Korean territory within our lifetime. But something needs to give, and for decades, people like me have been banging the drum (to no avail) that we need to solve this problem by legalising the Missing Middle. Or in simpler terms: by slowly, iteratively evolving our cities from detached suburban housing, to housing that is slightly more dense: Missing Middle typologies.

But here’s the rub — a constellation of annoying issues that touch everything from the economy, land values, construction costs, systems of governance and practical, real world spatial complexities — are all aligned to ostensibly ensure this type of housing renewal almost never happens in established urban areas.

What is the Missing Middle?

Depending on who you ask, the "Missing Middle" refers to a range of housing types that fall between traditional single-family homes and medium-scale apartment buildings. These include duplexes, triplexes, townhouses and low scale apartment buildings.

Why should we want the Missing Middle?

When it’s at its best, The Missing Middle creates a preferable level of density for how cities function, in that it allows many more people to live close to public transport, community infrastructure and employment centres.

The Missing Middle is also a nice-feeling compromise between high density living and the suburbs. They can come with many of the perks of owning a house. If you have a terrace home, you can still own land. Terrace homes are also incredibly flexible as a typology — they don’t have to be a dog box. If you want, a terrace home can have 7 bedrooms, a backyard, a garage, a pool, a shed, the works!

Missing Middle neighbourhoods also don’t feel as claustrophobic as being surrounded by high rise apartment buildings sometimes can.

Why am I writing this article?

All around the world, governments set ambitious urban growth and renewal targets, aiming to accommodate most of projected new dwelling growth (often around 60-75 per cent) within the existing urban footprint, intending to encourage the creation of the world that I just described – less new greenfield suburbs and more densification of existing urban areas.

The problem is, infill renewal is inherently more difficult, risky, expensive and complex. There’s a reason greenfield development always ends up doing the heavy lifting in delivering growth — it’s the path of least resistance.

For as long as I’ve been paying attention, these renewal strategies have been explicitly stating this goal, and mostly failing to meet it. Why is that? Surely it can’t be all the NIMBYs fault?

I am writing this to set out some of the reasons I’ve observed why this happens and offer some ideas on how things could be done better.

I’m not by any means saying this is a comprehensive list, so by all means, sound off in the comments if you’ve got more. I’ll even add it to the article if I agree.

Why is the Missing Middle… Missing?

Please, enough scene-setting! Let’s get into it.

Missing Middle renewal projects = higher risk / lower reward

The Missing Middle is indeed missing from Australian cities because these projects are an inherently higher risk / lower reward undertaking from a development feasibility perspective.

The lower number of dwellings in these projects means that there are less opportunities for construction efficiencies and economies of scale than you’d get on a higher density project. Meanwhile, the density is still high enough that certain elements move to a higher expense category, such as moving from at-grade parking to basement / podium parking or having to provide lifts.

Now add that additional cost and risk to the task of finding sites that can be amalgamated, getting planning approval, going through community consultation, demolishing existing structures, and then starting construction. You can see why developers prefer to pursue projects with a higher potential output for all of those additional headaches.

This point around feasibility is being made worse due to the escalating cost of construction in recent years. Right now, the construction labour shortage is leading to massive construction costs, and an ever-shrinking pool of buyers who can afford new homes. So until these factors normalise, any Missing Middle renewal is unlikely to anything approaching “affordable”.

Desirable neighbourhoods have higher land values

Where Missing Middle typologies are built in desirable neighbourhoods with high land values, it tends to result in an end product that is geared towards the high-end luxury market. While this is still desirable in that it increases aggregate supply, it means that privately-delivered renewal of Missing Middle typologies is much less likely to provide affordable housing in desirable locations — and that’s supposed to be the goal!

So how we define the breadth of what homes are classified as Missing Middle typologies is critical in delivering more affordable housing via the private sector. If the definition can be expanded to include more efficient buildings of up to 6 storeys, this improves the prospects of delivering some affordable housing in these more expensive locations.

Every city is a beautiful, unique snowflake

As cities evolve, the macroeconomic context of any given era organically gives rise to different housing designs and urban structures that are emblematic of their time.

In Canberra for example, the Griffin Plan's Garden City philosophy established generous inner city suburban blocks of around 700m2 with large front setbacks, while newer greenfield blocks on the urban fringe are significantly smaller at around 350-450m2 with tiny side setbacks.

This urban evolution went a little bit different in each and every city, so you can’t just cut and paste the exact same set of buildings on these varying lot sizes — it just won’t do.

Those tasked with devising renewal policies for entire cities, regions — and in some instances, countries — are often tasked with finding a one size fits all approach for what are very different contexts. For this reason, macro-scale strategies are often under-resourced to grapple with the enormity of this task.

But when done right, renewal strategies are based on the realities of each area in question’s unique block structure, in order to gear the design of future homes to work within the local block structure — giving these projects the greatest chance of success.

Block amalgamation is unpredictable

The delivery of many types of Missing Middle housing often requires two or three suburban blocks, adding an extra degree of difficulty and cost in the process of finding multiple sites that can be amalgamated.

It is often for this reason that renewal strategies relying upon the densification of suburban single family housing areas often deliver underwhelming results. Even without NIMBYs, neighbours just aren’t that likely to want to sell their homes at the same time. It’s also kind of impossible to make any predictions or assumptions on.

This issue can be mitigated through updating planning instruments to enable typologies that can be delivered on a single typical block and therefore do not require lot assembly. Meanwhile, larger buildings can be focused towards areas of consolidated ownership, along with more traditional renewal stock, like ageing centres and industrial areas.

It’s also an argument for legalising the Missing Middle everywhere. If the take-up rate for block amalgamation is so fraught, widening the net to include all relevant suburbs is a way to ensure that anyone who wants to pursue this path has the opportunity.

Economics has a big role to play here too. The reality is, that very few people will pay the fixed costs of amalgamating lots unless the value uplift is significant. This is why any upzoning strategies need to be informed by the land values and the feasibility of development in those locations. Larger value uplift from higher density zoning overlays, applied across a large area will see higher uptake.

There have been a few attempts to create incentives for property owners to amalgamate their blocks, but I’m yet to hear of any that have produced notable results or that are transferable to the Australian context. Am I wrong? Let me know in the comments and I will correct the record.

Retrofitting planning controls is a minefield

Let’s say you convince the community to let you rezone existing suburban areas for Missing Middle housing, bravo! Take a second to congratulate yourself and then get right back in the trenches, soldier – the war has only just begun.

There are multiple international examples of governments that have acted to legalise Missing Middle typologies, only to have their dreams get strangled in the cradle due to the conflicting elements of every other remnant planning control still lurking in the shadows.

To this end, all the other planning controls such as parking requirements, minimum lot sizes, setbacks, site cover and many others also need to be revisited to ensure that they’re actually geared for the housing we’re trying to build. Simply allowing Missing Middle typologies is not enough.

If possible, it is a simpler and more direct Gordian Knot-style approach to avoid trying to retrofit existing land use zone codes at all, and instead create dedicated Missing Middle codes and rezone the areas in question.

The NIMBY Supremacy

Here at The Emergent City, we have done our share of NIMBY-bashing, so I won’t belabour the point, but it would be a weirdly incomplete article if I didn’t mention them. I’ll even try to be more charitable this time.

The nub of the issue is that it is the life goal of every single Australian to:

a) Buy a detached suburban home; and

b) Pour their entire accumulated life’s wealth into making that home as expensive as humanly possible, in order to eventually fund their retirement.

In this context, asking communities to tolerate something as benign as a duplex is perceived as an existential threat to your accumulated life’s work and the luxury of said retirement.

So while everybody seems to agree that it would be nice if housing were more affordable, this is under no circumstances to result in any reduction in the value of their home, or any change to their neighbourhoods. To any politicians reading this I say, good luck with that.

For housing to continue behaving as an investment, prices must go up. Unfortunately for us, housing is also how we stay out of the rain. When the price of shelter goes up, the tent cities grow.

To borrow a simply perfect quote from the blurb of this Strong Towns video, the crux of the issue is this: Housing can’t be both a good investment and broadly affordable — yet we insist on both.

To briefly defend our dear NIMBYs, Australian property has almost always functioned as the primary vehicle for social mobility in Australia — so breaking that cycle is no small ask. If you’re advocating for an entirely different economy, you should expect some pushback, and this is precisely why NIMBY-bashing is unproductive. We must not hate the player, we must hate the game.

These toxic incentive structures bring us to the local politics angle. NIMBYs are financially incentivised to use the state apparatus to preserve the status quo. They inherently have more time and resources to devote towards lobbying local government, with the goal of freezing their neighbourhoods in amber — essentially making each and every suburb a UNESCO heritage-listed village.

I don’t have any great solutions for this, because there are none.

Still, things can be done that may or may not make a difference. Community sentiment towards Missing Middle housing can be improved through authentic and genuine community engagement and education initiatives, transparent planning processes, meaningful consultation around preservation of key neighbourhood character elements, investments in infrastructure and through delivering best practice demonstration projects.

Local planning instruments are a perfect tool for preventing Missing Middle renewal

Local planning instruments often include place-specific strategies as they relate to targeted areas in a given city. It can vary whether these instruments have a role when assessing development applications, but they usually do provide opportunities for communities to advocate for impediments to Missing Middle renewal through a range of mechanisms, such as heritage and character protections.

Strategies to enable Missing Middle development in targeted locales must factor in these protections and their impact upon projected growth. I.e. Don’t make your growth targets rely on the renewal of areas that have no hope of renewal — it’s self-defeating.

Infrastructure first; upzone last

In Australia, we tend to do urban renewal in the wrong order. It typically goes like this:

Area is slated for renewal and gets upzoned to allow for higher density housing.

Private developers buy up sites, iteratively redeveloping the area in bite-sized stages according to demand.

As the precinct organically renews and the population grows, infrastructure begins to strain. Roads get congested. Schools get overcrowded. There is nowhere near enough public space.

Reacting to community outrage, governments invest in the extremely costly, time-consuming and difficult task of retrofitting a medium-high density neighbourhood with facilities and infrastructure.

This approach unnecessarily gives NIMBYs a legitimate argument: that more often than not, neighbourhoods slated for renewal aren’t equipped for a larger population.

Urban renewal is at its best when we lead with the infrastructure - making shrewd investments in the things we need, to set emerging communities up for success. In the long term, this approach is cheaper, easier, more sustainable and creates better communities, as well as opportunities for governments to see windfalls from value capture.

The catch? Leading with infrastructure requires a mindset and delivery model that is comfortable with putting significant skin in the game from the outset of a renewal strategy, while also getting comfortable with some redundancy over many years while the neighbourhood renews.

This would be fundamental change from the way things are done in Australia, where the hyperfinancialised nature of our decision-making means that we:

a) Couldn’t imagine building a train station where there wasn’t anyone around to use it, but also:

b) Couldn’t imagine sending a new train line through an existing suburb, because can you imagine the headaches?

To get there, we need to stop viewing every individual piece of infrastructure as something that needs to justify itself on its own merits, and instead see them as the vital veins and arteries that are necessary parts of a cohesive whole. A train line is not a business that needs to make money, it is a tool for the sustainable growth of cities.

Byzantine planning processes can scare developers off

I wouldn’t say this is the most important one, but the worst examples of overly-lengthy and bureaucratic approval processes can definitely deter developers, especially when the profit margins are already questionable. Anecdotally, Queensland is currently benefiting from an exodus of solar farm projects from New South Wales and Victoria for this very reason.

These processes can of course be improved through streamlining approval processes, providing clear and predictable timelines, and offering incentives for projects that meet certain criteria, such as affordable housing. Critically, governments should encourage early engagement with community stakeholders to address concerns upfront and avoid lengthy appeals processes.

Hire me to do this for you

This type of stuff makes up part of what I do for a living, so if you are involved in renewal issues and are thinking “let’s get this guy on the case” — actually do that! I want to be on the case.

Another great article, thanks! I'm always very impressed by your work and learn a lot from your thoughts. You'll have a book soon!

hmmmm much to think about.

Firstly I was the guy annoying you on reddit about writing more posts, so i'm glad that you're back. Hope all is well with your new baby as well.

This article gave me a few thoughts.

Firstly i'm glad you mentioned Canberra. I used to live there and thought it was a bit odd that there were detached houses a stone's throw from the centre of town (if you call Civic the centre of town, that's debatable), while out on the outskirts of the newer suburbs (Gungahlin, Belconnen etc) had all the big towers going up. Sort of like an upside down city with density at the edges. Not real logical but it's what they're stuck with.

As for block amalgamation, we use land resumption/compulsory acquisition every time we build another dumb toll road. Could we ever use it for housing? Maybe our politicians aren't capable of selling that to voters, maybe they will when the streets fill up with tents.