Where the shovels aren't

A fractured construction sector reveals deeper structural fatigue and a system struggling to deliver.

Update: Thanks to the excellent work of

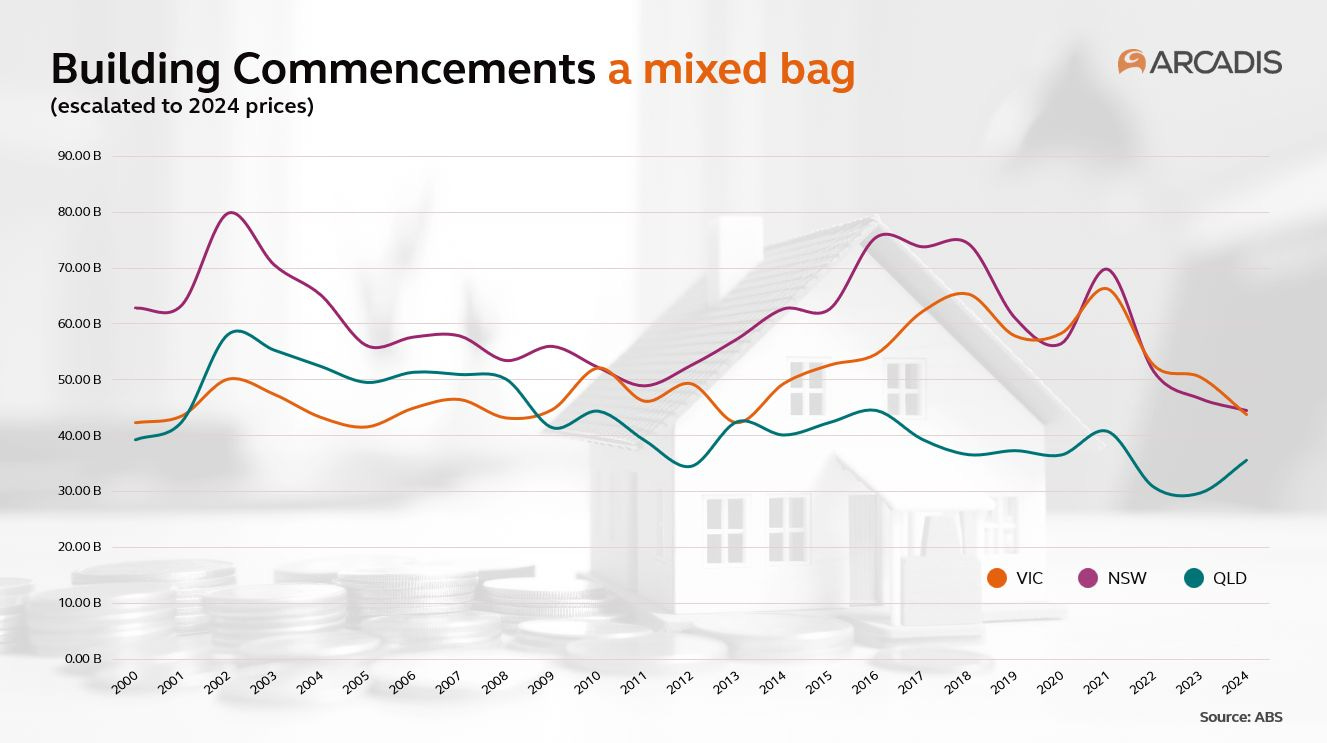

of the Land Supply Insight it turns out the data I based this article off was wrong, so I am resending it. How embarrassing for me! Egg on my face! etc. etc. I have rewritten it to reflect the right data. The key difference is the data now paints a still poor, but more more favourable than before picture of construction commencements across Australia’s eastern states, and even an improvement in Queensland.If you’ve been keeping an eye on construction data over the past few years, you’d be forgiven for thinking we’ve hit the bottom of the cycle. But while some metrics continue their downward spiral, others are showing some signs of life. It's not a collapse — it’s something messier.

The latest data for building commencements in the eastern states shows a construction industry pulling in different directions and buckling in some places.

Why commencements matter

Commencements are one of the only metrics that actually tell us anything concrete (sorry). Commencements mean projects that are not just being talked about, they’re not in the planning and design phase, and are not being lodged as a development application with Council. Commencements means projects that are actually commencing construction. Steam whistles blowing! Sod being turned! Actual men at actual work!

Commencements are the earliest and clearest signal of future construction activity. They tell us not what is happening now, but what’s coming. When commencements fall, it means fewer homes, fewer commercial spaces, fewer infrastructure projects will be delivered in the months and years ahead. The effects ripple outward: tradies sit idle, supply chains contract, and local economies that depend on construction industry lose momentum — sell your Icebreak stock right now. These aren’t just numbers on a spreadsheet, they’re early indicators of economic drag, housing undersupply, and lost capacity in an industry that already struggles to deliver at scale. When the pipeline dries up, so too does progress.

The numbers

New South Wales

Building commencements declined by 4.6% between 2023 and 2024. While that’s a relatively modest annual fall, the longer view is more concerning. Commencements are now down 21% compared to 2020, suggesting a persistent post-pandemic / inflation / high interest rate driven stagnation.Victoria

The slowdown is more acute in VIC. Commencements fell 13.2% over the past year, with a cumulative decline of 25% since 2020. A quarter of the pipeline has effectively disappeared in four years.Queensland

Building commencements actually rose 19.7% in Queensland between 2023 and 2024. While activity is still 3% lower than 2020 levels (despite the population increasing by 8% in the same period). Queensland at least appears to be defying the broader downtrend.

So to revise my original interpretation, this is not a total system-wide collapse (phew). There is pain, but it is not evenly distributed and the data still points to an industry struggling under pressure. The output picture still looks rather lean.

What is causing this?

The usual suspects:

Economic Uncertainty: Volatile interest rates, tighter lending conditions, and growing investor caution are creating a climate of indecision. When capital puts down their tools, tradies are not far behind them.

Cost Escalation: As I have been ranting about ad nauseam for the last couple of years, construction costs have surged in the wake of global supply chain shocks, inflation, labour shortages, and material price spikes. For many developers, the numbers just don’t stack up. An increasing amount of buyers simply cannot afford a new build, which is reducing the construction of new supply. I wrote about this phenomenon here.

Productivity Lag: Despite endless chinwagging about innovation (whatever that even means), the sector continues to struggle with systemic inefficiencies in project delivery. Time overruns and budget blowouts are still the norm, not the exception.

None of these problems are new, but together, they’ve accumulated towards an inflection point where the construction sector is still stagnating post-COVID, despite increasing demand. It is due to a greater degree of difficulty making projects financially feasible, to move them beyond the planning and design stage, through to actual construction.

Some ideas

What’s needed now is action:

Unlock Investment: Governments and the finance sector must work together to de-risk private capital investment in the built environment. This could take the form of targeted yet more guarantees, subsidies or tax incentives.

Lift Productivity: It’s long past time we stopped talking about innovation and actually did it. Building our capacity in modern construction methods, and offsite manufacturing is long overdue.

Tame Costs: Smarter procurement, supply chain coordination, and a rethink of material standards could help reverse the unsustainable rise in baseline project costs.

Streamline Planning: Inconsistent planning timeframes continue to create uncertainty for developers. Reforming these systems to support more predictable timeframes, will make it easier for developer to plan for things like cost escalation and holding costs.

Rebuild Workforce Capacity: The sector faces a skills bottleneck. Targeted training, apprenticeships, recognising migrant qualifications and strengthening migration pathways are needed to ensure labour isn’t the constraint on recovery.

Coordinate Public and Private Pipelines: Right now, too many projects exist in isolation. Aligning public infrastructure investment with private development on large precinct-scale projects can amplify efficiencies and reduce duplication.

Support Better Demand Signals: Policy levers such as build-to-rent frameworks, or institutional housing models can create better demand signals.

So we’re not in freefall, but we’re not fully over COVID either. The economy is very weird right now. The traditional levers for construction sector growth are no longer working in the way they used to.

For private sector projects to financial sense again, that’s right you guessed it — line goes up — dwelling values need to become less affordable.

But rather than seeing this as the solution, this to me is the Big Problem:

The Big Problem

We keep trying to build our way out of the housing crisis via the private sector alone, in an economic environment where it just doesn’t seem possible — all the while missing the fact that there is a growing caste of people in this country who cannot afford a new build.

Due to the impossibly unfeasible politics of reducing dwelling values, the major parties only have one answer to the housing crisis: “Supply! Supply! Supply!”. The idea being that we’re going to empower the private sector to build our way out of the problem without — and this is critical — pissing off a single voter.

That doesn’t seem to be working out, so what now?

The beatings will continue until morale improves.

Or!

We could start laying the foundations for a parallel housing market, that doesn’t rely on endlessly rising asset values to house people — like we used to do in the 50s-80s.

It’s time for a massive, sustained investment in public housing. We need to build towards a separate parallel housing market that serves the need of the growing caste of people whose needs the private sector is struggling to serve.

In my mind, this is the only card left to play. The only solution left that doesn’t require current dwelling values to go down — which means it’s actually possible to do (politically).

And we need to get moving today because this stuff moves really, really slowly.

Don't disagree with the premise that we need a massive, sustained investment in public housing (every suburb should have at least 5% housing stock). But the pessimist in me wonders where all this money (let alone all the other bits and bobs) will come from. Governments worldwide suffer from a lack of revenue and I see no appetite for tax reform that can turn this around. On the other hand the world seems to be awash with private equity capital and they certainty won't be interested in public housing, unless there is some sweet deal attached.

One way I could see it happening if the Federal and State Governments get together in a version of Mission Economy (https://marianamazzucato.com/books/mission-economy/) that is locked into a future Commonwealth-State Housing Agreement. In particular it can seek to focus on three main outcomes:

1. Improve the share of good quality and appropriate public housing stock (well, dah!).

2. Use this project as a means to focus on getting people out of hazardous areas (e.g. flood and fire prone area). While not all these people will be candidates for PH, some will be (renters living in the lower cost housing); and others can take up opportunities afforded by new development. I have been a fan of Transferable Development Rights (TDR) as the means to facilitate moving dwellings out of hazardous areas and rebuilding at greater density in more appropriate and nearby locations, whilst not requiring expensive buy backs (obviously some money has to trade hands).

3. Modular homes should be compulsory in any TDR deal. This is where the private sector can be involved and R&D tax write off should be maximised to encourage firms to go all in on developing and fine turning this form of dwelling construction, especially at density. I believe high rise timber construction is now possible and is well advanced in European countries. Ideally the terms of the agreement should be favoured towards Australian companies where the profits and IP can be retained within the country.

With these 3 things there becomes a much stronger and compelling case for Joint Government intervention to increase the share of PH, which could be expanded upon over time to include more affordable private housing (owner occupied and rentals).

And finally, in (Dr) Geoff I trust. An analytical mind.

Typical East Coast chauvinist: gives us stats on the only area of the country that really matters to him, to hell with WA and SA and the NT and Tassie.