Apologies (again) for the radio silence, dear reader. My life has been a waking nightmare since about November when my son entered the festering, writhing nexus of unseen contagion that is the typical suburban daycare. Please, send help.

I am writing to you today about a Man On The Internet called James Howe.

James Howe is a furniture designer who has built a large following on Instagram commenting on the absolute state of housing in Australia. He does this mostly from the perspective of a designer, critiquing the aesthetics of modern housing design and construction against that of the past.

I don't mean to focus on him so directly, because I have enjoyed the vast majority of his videos. As a fellow design professional, there is definitely a catharsis in hearing someone definitively and publicly branding something shit as "shit". He’s also quite funny.

And while he does present himself as being a kind of heterodox, Bad Boy Truth Teller, I've chosen him as a focal point to write about, because his general Constellation of Opinions are actually quite commonplace amongst the public, which makes his arguments worth addressing.

So James, if you are reading this, nothing personal mate! I think your furniture is beautiful.

Anyway!

What James Howe is right about

Just to be as efficient as possible with the scene-setting, he makes the following claims that I have no issue with:

Most new houses aren't as nice as most old houses.

Knocking down nice old houses to build gauche new McMansions is bad.

The state of the housing market in Australia could be a lot better in so many ways.

So now that we've dispensed with the pleasantries, let’s get petty.

What James Howe is wrong about

While most of James' content is focused on making the above critiques, he has also built upon this platform to make other critiques of the housing market too. Namely:

The "diabolical hell-hole"-like quality of new masterplanned communities

The knocking down of existing homes to build higher density housing (e.g. townhouses).

On the second point, I have already written extensively on why it's important that we progressively densify existing inner suburbs through urban renewal. So at the risk of writing a 10,000 word manifesto, I am going to ignore that argument in order to focus more on the first point. If you want to read those articles, see below:

In this article, I'm going to use James’ videos as a stand-in for this type of widely-held opinion of new masterplanned communities, to argue that while people aren’t wrong to criticise some of these neighbourhoods from an aesthetics and lifestyle point of view — that this critique ultimately doesn't get us anywhere useful or tell us anything interesting.

We need to talk about Mickleham

James made a post about a new suburb on the outskirts of Melbourne called Mickleham. Mickleham appeared in the news when somebody snapped an unflattering photo of it from a plane. In typical fashion, James did not hold anything back in his blistering critique:

"A lot of people are pointing out that this is just a diabolical hell hole (and that) this is just becoming the new standard for Australia - a country where we've had, like, really beautiful houses, backyards, barbecues (and) you know, backyard cricket and we're just throwing it in the bin."

James is right. New communities on the fringe of Australian megacities are getting denser. Backyards are getting smaller. Said as charitably as possible, the housing in Mickleham isn't as beautiful as that of the past.

Ok, same team so far, what's the point of this article again?

The Designer Mindset cares only about design

Like James, I too come from a design background, so I am very familiar with The Designer Mindset.

This is a mindset and worldview that is fine-tuned to prioritise aesthetics and functionality above all else. Being hyper-aware of aesthetics is what designers are good at, and in most cases it is the main skill they were born with.

Being a designer is also much more of an identity than other careers. It’s not just a career, it’s a calling. Where an accountant might define themselves by their hobbies, designers are designers. It’s both their job and what they’re into. It defines everything about them. Their homes, their clothes, their cars, their hair, the way they talk — everything! It is the hammer, with which they look to hit every nail. Every problem is just a design problem awaiting a design solution. And we need designers! We need them to create beautiful things, buildings and places. It’s why the furniture that James makes is very beautiful.

Designers are at their best when saying, "Wouldn't this be nice?" as they draw the prettiest picture they can. They are even great at saying why it would be nice. But what designers are really bad at, is understanding how their pretty picture might come to life.

To the designer, the how is grubby business. Numbers? Spreadsheets? Logistics? Compromises? No thank you.

I’ve found that most designers ultimately do not want to dirty their hands with such unpleasantness. Their joy mostly comes from creating beauty. The joy of successful implementation is an entirely separate type of satisfaction. Yes good designers will consider the how as best they can with the information that is available to them, but so many decisions and outcomes are already predetermined before the designer even gets a phone call.

But sitting in the warm, familiar comfort of the design world, saying "Isn’t everything ugly these days?" isn't interesting or useful.

The problem is of course that the housing crisis isn’t a design problem. It is a big, complex, multidisciplinary, macroeconomic, Wicked Problem — a small component of which is related to design. Therefore, for a design critique to be interesting and useful, it needs to understand and interact with the rest of the problem.

It is of course perfectly fine to notice that some things were better in the past — after all, I do it here all the time. But what irks me about the Designer Mindset is the fundamental lack of curiosity. The Designer Mindset brands things as ugly and shit, but doesn't feel the need to ask why?

Why are we as a society producing less beautiful homes than we used to?

Why are back yards getting smaller?

Why are neighbourhoods getting denser?

Why, despite all this, is housing more expensive than ever?

If you press these people for an answer, they inevitably have one at the ready:

The Greedy Developer.

The Greedy Developer Hypothesis

This is a narrative that you can find everywhere. I call it the Greedy Developer Hypothesis.

It's one of the few public opinions that seems to enjoy bipartisan support. It is the knee-jerk reaction of the everyman. Everybody hates developers, because they are so very greedy. How many JetSkis are enough, developers? How many JetSkis are enough?

James Howe is no different. I quote him in one of his comment replies:

"It's cooked. People getting rich by persuading people they only deserve a hot ugly little box to live in."

In another video he asks:

“Am I the only one who has noticed that as houses have become cheaper and cheaper and cheaper to build, they have become more and more and more expensive?”

At the core of this argument is the assumption that developers are cramming all of these houses together with tiny back yards and so close together, in order to make more money than they otherwise would. The Greedy Developers, people will have you know, are deliberately doing this as a kind of Evil Business Strategy.

Let's assume this theory is true for a second.

In this world, all of the major developers in Australia have conspired to:

Drive down the size of land parcels,

Lower the aesthetic quality of new houses,

Reduce the size of new houses and back yards, and;

Sell them at a higher price despite the above.

They did this of course, to make precious money, by driving down their own operating costs while charging higher prices to buyers for a lower quality product. So greedy!

If this were true, then there is a golden, multi-billion dollar opportunity waiting for a hypothetical Nice Developer. All this Nice Developer needs to do is sell the kinds of houses that James likes, on generously-sized blocks, at an affordable price and they would become an overnight success. Simultaneously, every Greedy Developer would go bankrupt within a few short years. After all, who would buy one of these hot ugly little boxes when a far superior, cheaper alternative was available?

The Nice Developer doesn’t even need to be nice! They just need to want to make a lot of money making lots of people very happy. Shouldn’t be too hard to find right?

Am I claiming that there is no such thing as a Greedy Developer? Certainly not.

But the premise of the Greedy Developer Hypothesis requires two things to be true at the same time:

That all developers must be Greedy Developers, and;

That there must be simultaneously zero Nice Developers.

There only needs to be one Nice Developer to uncover the grand conspiracy of the Greedy Developers. It is only the complete absence of Nice Developers that allows the cartel conduct of Greedy Developers to continue unabated.

The past is a different country

There is a saying I love, "The past is a different country".

It means that once a generation or two goes by, a country becomes different in almost every way. Different economy. Different demographics. Different advantages. Different problems. Different preferences. Different culture.

Have you ever wondered why most comedy doesn't age well? Or why people from different cultures have a different sense of humour? It's because comedy is about tapping into a specific moment within a cultural context. Once that context is gone, the jokes don't work anymore. Edgy new jokes become hacky old jokes.

Abe Simpson once summarised this perfectly:

I used to be with ‘it’, but then they changed what ‘it’ was. Now what I’m with isn’t ‘it’ anymore and what’s ‘it’ seems weird and scary. It’ll happen to you.

Back to the topic at hand, the Australia that produced the beautiful homes that we know and love was a completely different economy and culture. A different country. Unfortunately for us, that Australia is long gone.

Many of us are still coming to terms with this.

Australia is a different country now

That Australia of James' youth was blessed with abundance and opportunity. An Australia where rampant inflation hadn’t yet undermined everyone’s wages. An Australia with lower student debt. An Australia where building a new house cost significantly less as a proportion of the average income. An Australia where the labour of skilled artisans was cheap and abundant. An Australia where durable, high quality materials were locally available and cheaply sourced. An Australia where well-located, generously-sized blocks were still undeveloped. An Australia with slower economic cycles. An Australia with less real estate speculation. An Australia where public housing made up a significant proportion of new builds. An Australia where the Peter Dutton could buy his first house at 19 and feel like a genius while doing so. An Australia where average, unremarkable people with very normal jobs could easily afford high quality housing and ride its value all the way to middle class wealth.

In other words, a different country — and dare I say, a better country.

I have the experience of working in the development industry and am endlessly involved in conversations around cost of construction and feasibility. And take it from me, the cost of construction has gone through the roof. Nothing is stacking up. It is incredibly hard to turn a profit right now, especially if you are in the business of providing housing for the lower end of the market.

The only types of projects getting built right now are:

High end luxury homes and apartments,

Retirement villages, and;

Places like Mickleham that people like James hate.

Simultaneously, we have:

Low housing approvals,

Even lower quantities of housing getting constructed,

Construction costs still increasing, and;

Builders, developers and contractors going broke at record rates.

If this is what developer greed looks like, they're not doing a very good job.

James comes so close to stumbling upon these truths in some of his videos — noticing that a house he didn't like was:

"Designed by numbers, in other words, designed to make the most amount of money with the least amount of spend".

Here, James discovers how the private sector works. People who sell things do indeed try to make a profit within the parameters of what their customers can afford. They do this so that they don’t go broke and have enough cream on top to begin the process again — and yes, so they can afford a JetSki.

Home buyers have less purchasing power than ever

Australia's economy is really quite bad, especially right now, and especially for the working class. Yes, we have mining, but the rest of us are basically just sitting around making websites for each other. We are not a serious country.

When it comes to housing, we are collectively poorer than we used to be. What James is really noticing in his critique is our collective decline as a nation. Sad!

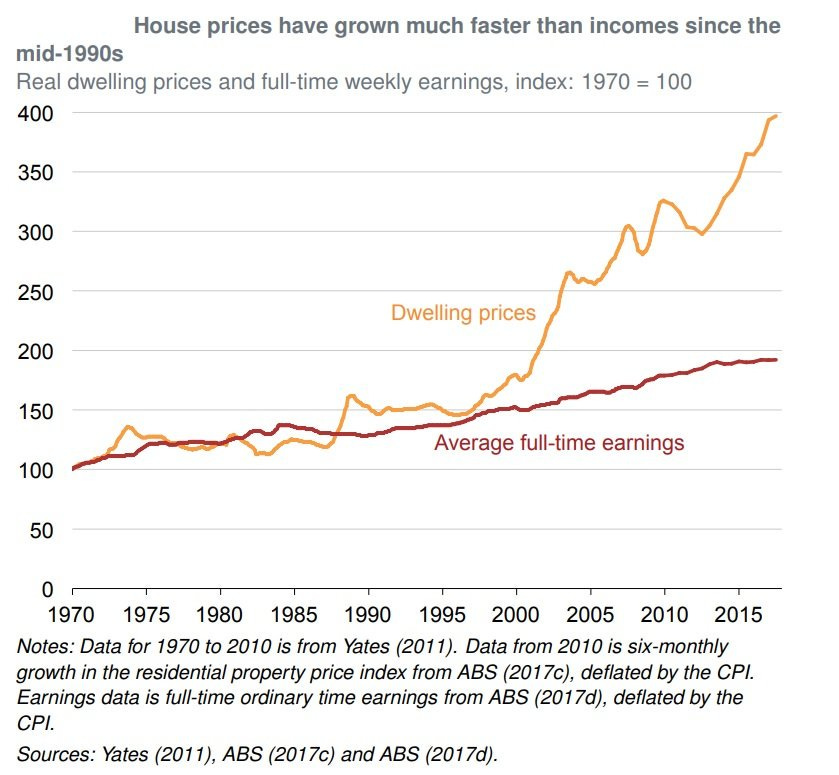

Since around 1999-2001, the relationship between the cost of the average house, versus the average wage has been completely decoupled. House prices rose, while wages couldn’t keep up.

Today, it costs the average Australian wage earner around 11.5 years to save a 20% deposit for the average Australian house. In the 80s it took a bit under 3 years.

This, my dear, sweet designers is why housing costs more than ever, despite being smaller and less pretty.

The Australians who buy these houses can't afford better ones. They certainly can’t afford the ones that designers like James like.

If it weren't for these Micklehams that are so maligned, these people would be renting or living with their parents. If it weren't for the developers producing these communities, nobody would be providing new housing for the working class. And contrary to popular belief, new apartments are not cheaper than new houses — they are significantly more expensive (at least right now).

So designers, repeat after me:

Blocks and back yards are smaller because buyers have less purchasing power.

Neighbourhood are denser because buyers have less purchasing power.

Housing is lower quality because buyers have less purchasing power.

If developers could produce a nicer house on a bigger lot that lower income people could afford, I promise you, they would be foaming at the mouth to build it.

These arguments reveal an almost cartoonish level of cluelessness at the heart of the Designer Mindset. They just want everyone to live in beautiful homes like we used to — and the only thing standing in the way of that is a couple of greedy bad guys.

Case closed.

But it is simply not accurate to blame developers, builders and planners for the Micklehams of the world, when this is ultimately just the sausage that comes out the end of a very broken system. Developers can only work within the conditions set by the macroeconomic environment — which are incredibly tight right now. Need I remind you that the tent cities are growing?

Don’t hate the player, hate the game

Mickleham is not a byproduct of developer greed, it is the symptom of an economy being squeezed for all it is worth. So if you must blame someone, blame the last 30 years of complacent “leadership” (and the voters who supported them) that have brought the country to this dire state of affairs. We get the politics we deserve.

I want to be careful here so that I don't come across as one of these people that is all about saying "the status quo is fine, and the best we can do". If there's been one theme of this page it's that better things are possible, and like James, I also look to the past for proof of that.

However, it's very important that we direct our criticism in the right direction. Let’s not just look at the underwhelming sausage on our plate, spit in the face of the waiter and call it a day.

Instead let’s all of us be a bit more curious about how the sausage is made.

Bravo! What a piece.

A closer examination of urban development and housing reveals several counterintuitive realities:

1. The grand experiments of mid-20th century urban planning, particularly prevalent in the post-war and post-colonial era, stand as cautionary tales. The attempt to design cities from scratch, divorced from market forces and organic development, resulted in consistent failure. Top-down urban design proved fundamentally incompatible with human needs and behaviors.

2. The international architectural discourse presents an interesting paradox: while Australian suburban homes rarely feature in design magazines, Tokyo - with its market-driven development - is celebrated globally as an exemplar of urban cool.

3. The aesthetic quality of middle-class housing reflects a broader pattern in mass taste. The parallel with media consumption is telling: when gatekeepers were removed from media production in the 1980s, rather than gravitating toward high art, audiences overwhelmingly chose what cultural critics would consider lower-quality entertainment. The same principle applies to housing aesthetics.

4. Traditional housing affordability metrics mislead through oversimplification. Mortgage-to-income and rent-to-income ratios provide more nuanced insights into true housing accessibility. These measures have shown relative stability over time, with financial distress actually declining over the past two decades. Notably, such distress concentrates in regional areas rather than affluent urban centers.

5. Australian housing statistics challenge popular narratives about declining standards. Australians enjoy the world's largest median house sizes, exceeding even American dimensions, while maintaining stable homeownership rates.

6. The reduction in backyard sizes reflects economic advancement rather than constraint. In high-value areas, dedicating space to lawns represents an increasingly expensive opportunity cost, driving more efficient land use patterns.