The housing crisis is an emergency and we're not acting like it

How a multigenerational legacy of smooth sailing, political stagnation and cultural complacency sustains the housing crisis.

A hypothetical scenario:

The year is 2024. A small asteroid hits the Pacific Ocean, creating a tsunami that devastates the east coast of Australia - but also Melbourne, Perth and Adelaide for some reason.

As the ocean recedes, the extent of the damage is revealed:

122,494 people are experiencing homelessness, with 1,600 people being pushed into homelessness each month.

Australia’s rate of homelessness skyrockets to somewhere between the third and sixth highest in the OECD, with an estimated 424 homeless people dying on the street every year.

The national shortage of social and affordable homes jumps to 640,000 and is expected to grow over 75,000 over the next five years as the crisis deepens. Projections indicate by 2041, there will be 940,000 households with unmet housing needs.

In Queensland alone, 45,958 people are on the social housing waitlist, with 27,438 of those assessed as high needs.

377,600 households are in housing need, or 33,100 in rental stress and 46,500 experiencing homelessness.

Rental vacancy rates plummet to historically low levels of 0.90% (a healthy vacancy rate is considered to be 2.6% - 3.5%).

Emboldened by a national emergency, the Federal Government devises a bold solution: the Tsunami Housing Australia Future Fund (THAFF).

The THAFF is a $12.5 billion investment fund that will invest money in the stock market. Each year, the profits from that fund (i.e. how much it earns on the stock market) will be used to fund the construction of new housing, hopefully funding 30,000 social housing dwellings over the first five years (nationally).

On an unrelated note, the Feds will also spend $368 billion over 30 years for 8 submarines and lose $254 billion in revenue over 10 years on the Stage 3 Tax Cuts.

Wait... what?… That’s the response? I thought this was an emergency?

If your IQ is above room temperature, you’ll have figured out where I'm going with this - the only fictional part of the above hypothetical is the tsunami. Those alarming statistics are just the state of things in Australia right now. The underwhelming THAFF is just the underwhelming HAFF.

The 30,000 social housing units the HAFF tacitly promises to build over 5 years (nationally!) won’t even cover half of the rate the social housing shortage is projected to grow over the same five year period (by 75,000). It won’t even cover the current social housing shortage in Queensland.

In terms of ambition and scope, it is missing a zero.

But wait, there’s more:

As discussed in my last article, I believe we are also headed for a major labour shortage based on the confluence of the following factors in the coming years:

A worsening housing crisis, exacerbated by population growth;

Slowing construction activity brought on by inflation, labour shortages and high construction costs; and

Untold billions in planned infrastructure spending, siphoning construction labour into mega projects to the detriment of smaller projects (like housing)

To cut a long story short, I believe the above factors will severely limit the private sector’s ability to deliver anything approaching housing that could be considered affordable, in anywhere approaching the quantities we need - perhaps with the enduring exception of greenfield masterplanned communities.

The time for action is right now

Any course corrections will require at least 5 years to take effect, meanwhile the tent cities are growing.

The call to action being, if there was a time to think big, it is was a decade ago - but today will have to do. We are facing some Big Problems, which require Big Solutions.

While the most generous reading of the HAFF is that it is at best, a step in the right direction, I will not bless it with Big Solution status - not even close.

But why have the policy responses to date all been too little, too late and too short-sighted? And more broadly, why are we seemingly unwilling and unable to solve our own self-inflicted problems? How did we get here?

Australia is poisoned by a culture of complacency

To zoom out a bit, Australia has jealously protected its brand as The Lucky Country, crystallising our much truer essence as The Complacent Country.

Since WWII, we have largely managed to avoid participating in, or directly experiencing history (undoubtedly a good thing; history is awful) - making us ignorant to the inevitability of change and how challenges must be met proactively by proactive people, doing actual things in the real world.

Australia hasn't faced a Big Boy Challenge in a long time. We haven't had a serious problem to solve that has asked anything of us as individuals or as a community, which has cultivated our ignorance, our selfishness and the degree to which we are insulated from problems that do not directly affect us.

We must shake off this culture of stagnation

The post-online hypernormalised media landscape means that politics is now consumed as abstract entertainment to be enjoyed and certainly never something to be engaged in.

Social institutions that were once facilitators of political action like labour unions, fraternal organisations, churches and community groups have been eroded to the point of irrelevance, leaving us hyper-individualised, screen-damaged and paradoxically isolated in a sea of millions.

At some point, the news cycle began to reflect this, becoming the unending dumpster fire that nourishes the Attention Economy. For at least my lifetime, this was mostly without consequences that rarely seem to actually spill over into reality - giving entire generations the false impression that politics do not matter. The end result is the outsized focus on red-meat culture war issues, laden with symbolism and devoid of substance, at the expense of anything resembling real, impactful policy with Material Consequences.

It is through this unspoken, bipartisan agreement to limit the window of acceptable discussion to inconsequential symbolic issues, that difficult conversations about Big Solutions to Big Problems are avoided. Band-aids are carefully applied. Goats are ruthlessly scaped, cans are kicked down roads, while those poor, wretched frogs continue to boil.

This is the clearest symptom of a culture that is without ideas, imagination or ambition. Australians have become unable to conceive of anything better than the status quo and have lost all confidence in our ability to solve our own self-inflicted problems.

A moment of sympathy

Our motto here at The Emergent City is that we do not hate the player - we hate the game.

The acute state of the housing crisis marks the end of a multi-generation era of good luck and smooth sailing. The remnant politics carried over from this period are quite naturally conditioned to recoil from Big Solutions to Big Problems. After all, why risk upsetting the apple cart, when things have always seemed to work out?

For at least my lifetime, the Australian zeitgeist has rewarded an emphasis on managerialism, risk mitigation, public relations, messaging and above all else, maintaining stability. Our instincts have become seismographically attuned to be so conflict adverse that we flinch at faintest of rumblings. The roughly two-thirds of Australians who own land have benefited from this age of complacency more than anyone, and therefore quite naturally seek to maintain status quo at all costs.

To briefly defend this, The Managerial Mindset was a defensible posture when things were all tickety-boo. But Managerialism cannot meet the moment if and when Big Solutions are required to solve Big Problems - for that, we need Leadership.

Once Australia boasted an ambitious, aspirational Liberalism, where we punched above our weight and actually built things. Once we had the confidence to propose a bold vision and inspire Australians to follow. These days every political utterance is focus-grouped within an inch of its life, masterfully distilled to achieve the perfect balance of maximum fence-sittery and minimal boat-rockery.

Managerialism cannot beat the housing crisis

In the context of broader historical cycles, present-day Australians are The Knights of Summer - we have never known a Winter (which I am positing, is coming). We are this era’s peacetime generals - focused on career advancement instead of the gruesome means and methods of winning wars. And as with every war that follows a long peace, the peacetime generals will be swept aside when stakes are inevitably raised and we can no longer pretend the Big Problems are not in fact, big. Then and only then will we raise up the scrappy-but-capable talent from the ranks who are proven on the battlefield.

The question that always seems to come up in my articles rears its ugly head yet again - how bad will things need to get before Big Solutions are even publicly-entertained as serious ideas?

In the mean time, everything seems to stay the same, which is of course, unsustainable, because the world has this annoying habit of constantly changing.

The housing crisis takes place in reality

The thing about the housing crisis that makes it unlike some other issues, is that it takes place IRL: In Real Life.

Housing is significantly less abstract than other juicy issues like climate change, where it's like "oh no, an iceberg the size Paraguay just broke off Antarctica", but in the meantime you've just run out of toilet paper in a petrol station bathroom - sorry Antarctica, not today. Our brains can register that these things are happening, but they are not sufficiently inflicted upon us in a way resonates deeply enough to broil a mass politics from below.

I'm arguing that the housing crisis is different, because it concerns big, expensive and visible stuff and people in our immediate world. Many, many people are struggling right now.

The tens of thousands of new dwellings we need is real shelter for real people. Real people that will need real houses or they will be out in the real rain or living in their real cars on the real street… Real!

This is a crisis that must not go to waste

Former Obama-era Whitehouse Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel famously said:

"You never want a serious crisis to go to waste." Because they allow you a window of opportunity to achieve things that would otherwise be more difficult.

We are in a moment, right now, where the housing crisis is front and centre in the Australian imagination. Housing has never been more in vogue than it is right now. There are some pretty incredible TikTok influencers like Jack Toohey that are having a major impact in educating people on the issue. To the irritation of millions, this Christmas, throngs of Millennials and Zoomers will quote housing statistics at their parents, pointing at graphs between swigs of Yellowglen. What a time to be alive.

Update: Jack Toohey has joined substack - definitely give him a follow. Jack Toohey

These moments in history are rare and fleeting - political energy is fickle, jumping from crisis to crisis according to the flavour of the month. Remember the war in Ukraine?

To return to the premise of this article, if we were reeling from the immediate shock of a tsunami, Australia would be unified and laser-focused on fixing the damage. But because the housing crisis has been a much slower and more insidious undermining of the Australian economy, it has failed to gain an appropriate degree of national attention – until now!

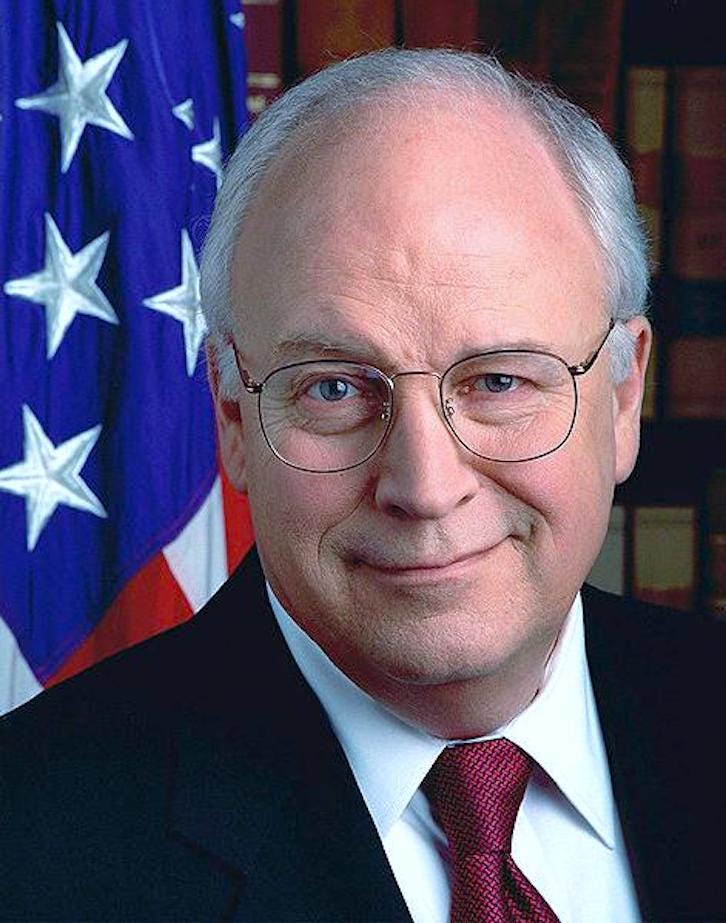

Look to semi-recent history for inspiration! If notoriously blood-soaked demon, Dick Cheney can use 9/11 to destroy several entire countries that had nothing to do with 9/11, surely we can use the housing crisis to build some houses for ourselves.

A change in the tone is long overdue

This too is a crisis that simply must not go to waste - a change in the tone is long overdue.

Those who understand issue should be framing this as a national emergency that calls for bold, heavy-handed and large scale solutions.

Discourse that nibbles at the edge of the problem will only beget more nibbling. Nibbling has been tried; we’re all nibbled out. We can spend the next 5 years agonising over how to fine-tune the perfect inclusionary zoning policy, or we can zoom out and notice that inclusionary zoning policies have never made housing affordable in any meaningful quantities, anywhere.

Unfortunately, this is not a problem that can be solved by changing a few rules. That ship sailed about a decade ago.

There are many policies that need to be deployed to address the housing crisis, but several dimensions of the issue have become a bit of a punching bag - including by me (I’m on a journey here). These scapegoat issues serve a convenient purpose by taking up an oversized amount of oxygen in the debate, while not leading to anything resembling substantive or ambitious policy proposals. Meanwhile the policy responses that (in my opinion) need the most attention are almost never even discussed publicly.

We need a massive, sustained public investment in social housing

As I’ve argued previously, the housing crisis is a Wicked Problem, which means the problem is not One Thing, and therefore the solution is not going to be One Thing. There is indeed a diverse suite of changes that need to be made across the economy and the regulatory environment - and we should make those changes!

However, in my journey to educate myself on this issue, I’ve come to believe that the single most important thing the Federal Government should be doing is undertaking a massive, sustained investment in building public housing. We need to get back to something approximating the quantities of public housing we used to build in the 50s-80s period.

We need to go Full Singapore. We need to become Viennese.

I’m going to spend my next article (or seven) making the case for this, and trying to educate myself on how this might work.

If you don’t want to wait, I suggest checking out the work of Cameron Murray, who is way smarter than me on this issue anyway. If you’re subscribed to me, but not him - my dear friend you are dropping the ball.

Subscribe to my Substack!

As a subscriber, you’ll get my full articles (complete with images) in your email inbox - sparing you having to go to the actual website or be lucky enough to spot my articles in your feed. For whatever reason I find this a much more enjoyable and consistent way to read the writers I follow, so if you have enjoyed any of my articles so far, please subscribe.

"For at least my lifetime, the Australian zeitgeist has rewarded an emphasis on managerialism, risk mitigation, public relations, messaging and above all else, maintaining stability. Our instincts have become seismographically attuned to be so conflict adverse that we flinch at faintest of rumblings."

Too true, but good luck with finding the solution. There was an article in today's Brisbane Time written by a young person about the future of Brisbane as part of an essay competition (https://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/national/queensland/brisbane-in-2050-the-world-s-most-sustainable-city-20231129-p5ens8.html). All very nice and you would like it to be true (apart from all that vegetarianism), but in your heart of hearts you can't see 25% of these things happening.

I think you are right about the plethora of manageralism and dearth of leadership, but how do you achieve leadership, when the path of manageralism is paved with gold and the path of leadership is often paved with disappointment and sometimes termination? In my working life I think I could count on one hand the number of good leaders that I experienced (and I don't count myself in that). There are others outside my circle that you can see as demonstrating good vision and leadership, but again they are few and far between and tend to get derided.

My political hero was Whitlam, but I wonder if he came about today, and we didn't have those reforms in place, how would he be received? Probably wouldn't get pass 1st base and we will be closer to America in our social well-being and housing situation than present day Australia.

In Queensland planning terms the best leadership I experienced was Kevin Yearbury (maybe before your time), but he had vision and drive, as well great communication as to letting you know where he wanted to take the Department and legislation and why. Leaders are born not made.

"Australia has jealously protected its brand as The Lucky Country, crystallising our much truer essence as The Complacent Country."

It's not well-known, but that was the original meaning of the "the lucky country." We were "a lucky country mired in mediocrity and shackled to its past." Funny how people stop quoting after the word "country."

The authour said that we were lucky to have such natural resources, but we were also unlucky to have them - because it meant we could get away with having mediocre leaders. A little more scarcity would do us good, because scarcity brings forth the imaginative and innovative people.

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/3305564-the-lucky-country