Can we please stop pretending the market can save us?

Construction is stalling, prices aren’t falling, and wages can’t catch up. So what now?

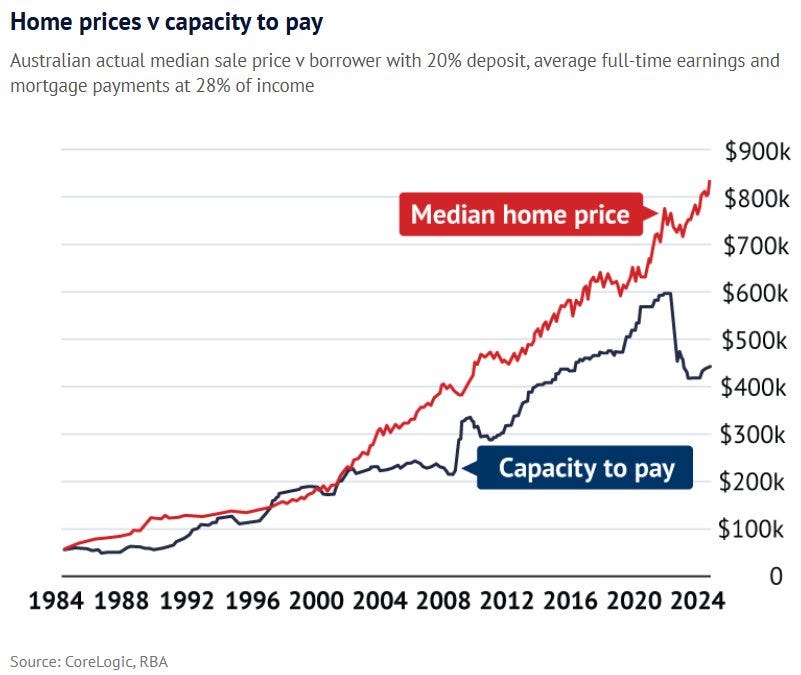

Once upon a time, Australian home values were in some way linked to the capacity of Australians to actually buy homes.

In 1975 the median wage was $7,600 and the median house price was $28,000.

A ratio of $1 of income for every $3.68 dollars of house cost.In 2025 the median wage is $72,000 and the median house price is $892,000.

A ratio of $1 dollar of income per 12.4 dollars of house cost.

Yes, comparing things across decades is a fraught exercise — the country was very different back then. Interest rates, taxes and unemployment were higher, but the fact remains that your parents (or grandparents) probably bought a home in their 20s on one income. In 2025, that idea is laughable.

Then, around the turn of the millennium, that relationship between house values and wages decoupled — and has since gotten significantly worse in the post-COVID era of construction cost inflation and high interest rates.

Housing prices decoupled from wages. Construction costs spiked. Interest rates skyrocketed. Borrowing capacity shrank, while prices stayed high.

My loyal readers will know that that none of this is news. But what still seems to surprise people is the extent to which there’s no easy way out.

The Australian Housing-Political Economy Trap

Two-thirds of Australian households own property. That’s not just a demographic fact, it’s a durable political majority.

For this reason, neither of the major parties are talking about deliberately reducing house prices — and understandably so — the political and economic risk of a sustained reduction in house prices is enormous. We’re talking an erosion in household wealth, collapsing consumer spending and investor activity, precarious retirement, a destabilised banking sector with the potential for mass foreclosures and bailouts.

Now you might be a young hungry renter licking your chops at the thought of mass foreclosures, but suffice to say that we should not be staking our hopes and dreams on the two-thirds of households voting for that. Not when the average Australian’s super, retirement, life’s work, idea of success and security are all inextricably fused with property values going up, forever.

“Ah, but what about immigration? Can’t we just cut immigration? Wouldn’t cutting immigration act as a pressure release valve?

I certainly think we should at least try gently reducing migration while the rental vacancy rate is so low — but let’s be real: Australia is screwed without a certain base level of population growth.

To be clear, I think the people who say that migration policy has nothing to do with the housing crisis are being dishonest — it obviously does, and you don’t need to be an economist to understand this. If you suddenly had a shrinking population, you’d need less houses, duh. And if you were only trying to solve the housing crisis in a vacuum, that is certainly an approach. But what the hawks don’t want to acknowledge is the broader cost that slashing migration will have.

Aside from mining, pretty much our entire economy is made up of demand driven services. We don’t make things here friend, we send emails. An entire nation, circling back and touching base — just sitting around making websites for each other. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again — Australia is not a serious country.

Economic complexity is a metric that measures the productive knowledge of an economy. It's based on the diversity and exclusivity of products a country exports, indicating how sophisticated and capable the economy is.

High economic complexity = diversified, resilient, good.

Low economic complexity = vulnerable, fragile, bad.

We have one of the least complex economies in the world. Not just the OECD, not just the developed world, the whole world.

In terms of economic complexity, our peers include the known powerhouses of Haiti (110), Togo (109), Namibia (108), Ghana (107), Cote d'ivoire (106) - Australia - 105, Botswana (104), Panama (103), Zambia (102), Senegal (101) and Russia (100).

You read that correctly. In terms of economic complexity, Australia is in the neighbourhood of at best an authoritarian petrostate (Russia) and at worst, a failed state overrun by roaming bands of machete-wielding gangs (Haiti).

So yes, cutting migration would make a dent in housing demand, but it would also undermine demand for just about every task that Australians do for money. Doctors won’t have enough patients! Barristas won’t have enough customers! The elderley won’t have enough carers! Graphic designers won’t have enough clients! Rap-rock DJs won’t have enough audiences! Property managers won’t have enough victims.

You may not like migration, but your job very likely depends on it. The cure can’t be worse than the disease.

So unless the hawks have a viable plan for fixing the fertility rate (they don’t), while at the same time massively diversifying our economy to be an order of magnitude more productive than we currently are, I’m afraid we’re stuck with migration for the foreseeable future. We are well and truly addicted to migration-driven growth, and that’s not great — but it is what it is.

I am very aware that there are People On The Internet who think I’m wrong about this, and think that a collapsing fertility rate is a perfectly worthwhile price to pay for affordable housing. I am aware of the arguments to be made around over-reliance on migration disincentivising innovation and improvements in productivity. But I’m yet to hear an argument that living in a shrinking economy is better than living in a growing one, other than “Japan seems fine?”

The economics of delivery are breaking down

As I have written ad nauseum, in city after city, housing demand is high — but the construction industry is struggling to deliver.

Why? Because most types of housing projects simply aren’t profitable anymore.

With rising interest rates, labour shortages, expensive materials, and razor-thin margins, developers can’t make the numbers work unless they’re building at the top end of the market, or large scale greenfield communities on the urban fringe.

It’s not greed. It’s not price gouging. It’s basic math.

Even if we upzoned everywhere and unleashed a flurry of fast-tracked approvals tomorrow (and we should do those things), the market wouldn’t suddenly start producing housing for low and middle income Australians.

Because it can’t. Because the buyers can’t afford what the builders are building.

Let’s stop dumping the responsibility to solve the housing crisis on the private sector

Despite the salacious title of this article, this isn’t an anti-market rant. The private sector does and should deliver the vast majority of housing in Australia, and always will. I have written several articles about how we can better enable the private sector to build more homes. But the reality is: we’re asking it to do something it just can’t do right now — deliver affordable homes at scale in a context where the economics just don’t support it.

So, if we can collectively accept the fact that:

We can’t bring home values down without major political and economic repercussions,

We can’t lift wages at a rate that exceeds housing inflation for decades on end,

And we can’t rely solely on the private sector to build our way out of this crisis —

Where does that leave us?

With one card left to play.

It’s time for a massive sustained investment in public housing

Ask yourself, what is The Government for?

Protecting rights, maintaining order — sure. But beyond those basic functions, the role of the public sector is to do things that we need, that the private sector either cannot do, or cannot do very well. This is why we subsidise general healthcare, while elective medical procedures like plastic surgery are a fully privatised market.

Right now, the private sector cannot build the amount of homes we need, because people cannot afford to buy them.

But the good news is, we only need to look to our own recent past for answers.

In the late 40s and early 50s, Australia embarked on an ambitious public housing program to address acute housing shortages. Under the first Commonwealth-State Housing Agreement (CSHA) from 1945 to 1956, public housing stock nationwide rose from near zero to 96,292 dwellings. By the end of 1956, over 14% of all dwellings built in Australia were public housing. Then, from 1954 through to the mid 80s, the public sector consistently constructed around 15,000 dwellings per year under successive Commonwealth-State agreements.

I’m not talking about your favourite social housing complex full of screaming meth addicts, violent ex-cons and charming vagrants (who yes, need homes too). These were normal homes for regular working families whose needs the private sector was struggling to serve. Sound familiar?

We need that scale of ambition again.

We need a parallel public housing market that does not require endless speculation to put a roof over peoples’ heads. Completely separate to the world of real estate agents, negative gearing and capital gains tax. A separate, complementary housing market where homes aren’t treated as investments, nor as welfare but as essential guillotine-prevention infrastructure.

A parallel public housing market doesn't require the current paradigm of endless price growth to be disrupted and it starts catching people from falling through the cracks that the currently failing system is generating.

It is actually politically and economically possible, whereas if you’ve got any politically viable ideas about how to stop Australians from treating housing as an investment — I’m all ears, friend.

The time Singapore went Full Singapore

Singapore houses 85% of its population in public housing and about 90% of those people own their homes. It’s not a mark of poverty — it’s a symptom of the rare combination of both functioning governance and state capacity. Their Housing and Development Board doesn’t just build homes. It drives innovation in design and modular construction methods which create efficiencies not currently possible in the private sector.

Now I know what you’re thinking — don’t let that 85% scare you.

We don’t need to get anywhere near that. Singapore is a city state on an island with a mostly-fixed amount of land. Australia doesn’t have those problems. I bring up the 85% because it is instructive as a direction of travel — showing us what we could achieve if there was a shred of ambition left in The Lucky Country.

There are no other cards left to play

We can keep propping up very broken system while we disenfranchise our children. We can keep praying that construction costs will magically fall. We can keep nibbling around the edges, tweaking tax and zoning settings and kicking the can down the road with Help To Buy schemes and Shared Equity programs.

Or!

We can confront the structural reality in front of us.

The private sector can’t build what doesn’t pay. Our politicians can’t let prices fall. Wages can’t keep up with house prices. And our economy is screwed without population growth.

So if we think it’s important that people have a roof over their heads — then we have to build our way there. Publicly.

We’re fresh out of bandaids. It’s time for Big Solutions to Big Problems.

"Aside from mining, pretty much our entire economy is made up of demand driven services. We don’t make things here friend, we send emails. An entire nation, circling back and touching base;" and so many of those service jobs are bullshit office jobs occupied by the otherwise unemployable, destined to be gobbled up by AI over the next few years. It makes one wonder what the Australian economy will actually look like in a decade.

I agree with the diagnosis, but not the conclusion. What we’re seeing isn’t market failure; it’s the market responding perfectly to the signals it’s been sent. And those signals, from zoning restrictions and tax incentives to artificially low interest rates, have all pointed towards inflating this particular asset class.

The core issue isn’t that the market can’t provide affordable housing. It’s that government intervention has distorted the incentives so badly that rational private actors are pushed into speculation, not supply. Introducing even more government spending, without fixing the underlying distortions, risks capitalising those subsidies straight back into land prices.

What to build, where, and how much should be driven by actual demand, not bureaucratic guesswork. The solution isn’t more state control, it’s coordinated deregulation. Let the market respond freely to demand by removing restrictive planning barriers, coordinating infrastructure delivery across the three levels of government, and refraining from policies that crowd out private investment in construction.

The more central planning we throw at this, the worse it will get. Just my 2 cents, fully acknowledging I'm not the housing expert...